This article was originally posted at Hoyden About Town on June 23, 2007, but has been substantially edited and updated for FWD/Forward.

This post started with me suggesting a FAQ on reclamation for the “Finally, a Feminism 101 Blog” blog: “But there’s a whole feminist magazine called Bitch and a book called The Ethical Slut, so why can’t I call you a slutty bitch?” I tried to write a one-paragraph answer, but things snowballed a little. Here’s my attempt at answering; I welcome yours, and have put in a few questions at the end.

I’ll open with a quote from Robin Brontsema’s “A Queer Revolution: Reconceptualizing the Debate Over Linguistic Reclamation”:

Laying claim to the forbidden, the word as weapon is taken up and taken back by those it seeks to shackle, a self-emancipation that defies hegemonic linguistic ownership and the (ab)use of power. Linguistic reclamation, also known as linguistic resignification or reappropriation, refers to the appropriation of a pejorative epithet by its target(s).

As with just about any topic in feminism, when stripped to the bone, reclamation is about power. The kyriarchal position is that people with power get to set the agenda, control the discourse, define people in pejorative terms, and decide what is or isn’t offensive – not only to themselves, but to others. They place themselves firmly in the subject position, and unilaterally assume the role of making decisions for less powerful people – the objects.

Feminism and disability activism are about turning that dominance model on its head in every realm, including language. One recurring feature of feminist discussion about pejorative speech is that the person with the lesser power gets to decide what is offensive to them, and that we should be listening to their voices, not those of the dominant group. In the case of sexist language, women have the voices that count, the voices that all need to listen to. For racist speech, women of colour. For classist speech, poor women. For ableist speech, disabled women. For anti-lesbian speech, lesbian women. Fattist speech, fat women. And so on, and so on.

Linguistic reclamation is the re-appropriation of a term used by those in power to demean and disparage those in a less powerful group. One way in which women refuse the object position and reclaim their subjectivity is to take back control of pejorative terms such as “bitch”, “slut”, “crip”, “gimp”, “chick”, “crone”, and “harridan”. Defused, a reclaimed word can become an in-group identifier, with a positive, powerful spin. It’s all about who gets to define “us” – “them” or “us”? Reclamation is about refusing to let others define your group, set the parameters, or establish the meanings. In some instances, reclamation is about reclaiming not just an arbitrarily-defined pejorative word, but about proudly reclaiming the pejorative meaning, when it is based in the fear of women speaking their minds, defending themselves, not letting their personal value be defined by their sexual worth to patriarchy.

EXAMPLES

Here’s a smorgasbord of examples of reclamatory language. Going by the principle of “In their own words”, I’ve pulled out snippets of discussion about or explanation of the specific reclaimed terms in a few cases.

Crip, Gimp, Mad, and Retard

When talking about reclamation and disability, “Crip” is the word that springs most readily to mind. Not only are individuals with all sorts of disabilities referring to themselves proudly and defiantly as crips, but an entire academic field is springing into being, dubbed Crip Theory.

When talking about reclamation and disability, “Crip” is the word that springs most readily to mind. Not only are individuals with all sorts of disabilities referring to themselves proudly and defiantly as crips, but an entire academic field is springing into being, dubbed Crip Theory.

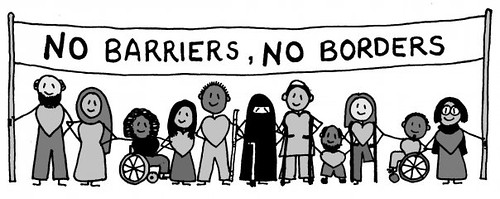

Crip theory takes the social model further and critiques disability theory. Rather than aiming to normalise disability and help disabled people to “fit in” to society as disability theory and neoliberalism do, this theory argues that society itself needs to be radically changed. Crip theory argues that disabled people are transforming our world into a more democratic, diverse, flexible place — by resisting oppressive social structures and calls for normalisation and assimilation, by living with pride and self-esteem, by speaking about their experiences of pain and pleasure, by expressing their sexuality, and by forming communities of support, love, activism and interdependence.

(Women, Disabled, Queer: Working together for our sexuality and rights, AWID International Forum 2008, via Creaworld.)

In “How dare I say ‘crip’?”, Victoria Brignell writes of her use of the word “crip:”

The crucial difference now is that it’s disabled people themselves who are using the word.

It’s part of a trend towards “reclaiming” language for our own purposes. We know full well that when we say the word crip, it will shock and startle – or at least raise eyebrows. It will grab able-bodied people’s attention and make them take notice of us. It forces able-bodied people to confront our disability. Whereas in the past able-bodied people used the word against us, we are now using it against able-bodied people. […] it’s when disabled people themselves use the word that it has the most desirable impact. When it comes from our lips, it becomes a linguistic tool in the struggle for the social inclusion of disabled people.

Eli muses about the etymology of the word “crip” in “Thinking about the word crip”:

I know where crip comes from in disability communities—the long histories of folks who have had cripple used against us. We have taken the word into our own mouths, rolled it around, shortened it, spoken it with fondness, humor, irony, recognition. And yet I can’t remember the first moment I heard the shortened, reclaimed version (nor, for that matter, the longer pain-infused original), when I adopted it as my own, started calling myself a queer crip. What are the specifics to this history and etymology? Who said it first in which spaces; how did it catch on; when was it first written down as a way of inscribing pride and resistance; how did it come to be passed from person to person over the years so that now I find myself thinking, “But didn’t crip just arise organically from disability communities, movements, cultures?” These are the questions to map out personal and communal etymologies that have very little to do with the Oxford English Dictionary, often thought of as the final authority on the history and etymology of English words.

Confluere carries a series of buttons declaring “Lame is Sexy”, “Lame is Good”, “Fuck Pity/Crip Pride”, and “Crips & Trannies Need to Pee Too”. Gimpgirl markets a variety of merchandise at: No Pity City, where those at the intersection of feminism and disability activism can assert their pride. There are many reclamatory blogs, from Bad Cripple, Crip Chronicles, and and Cripchick to Crip College and Crip Critic. And it doesn’t stop there – check out The Gimp Parade, the gimp_vent community at Livejournal, Gimp on the Go travel magazine, and the very active GimpGirl community.

Confluere carries a series of buttons declaring “Lame is Sexy”, “Lame is Good”, “Fuck Pity/Crip Pride”, and “Crips & Trannies Need to Pee Too”. Gimpgirl markets a variety of merchandise at: No Pity City, where those at the intersection of feminism and disability activism can assert their pride. There are many reclamatory blogs, from Bad Cripple, Crip Chronicles, and and Cripchick to Crip College and Crip Critic. And it doesn’t stop there – check out The Gimp Parade, the gimp_vent community at Livejournal, Gimp on the Go travel magazine, and the very active GimpGirl community.

Continue reading Reclamation: thoughts from a fat hairy uppity lame bitch

This obituary has been provided by Marion May Campbell, who supervised Barbara Moore’s thesis, The Art of Being a Tortoise: Life in the Slow Lane. The thesis is being edited for submission for a Master of Arts by Research in Creative Writing at the School of Culture & Communication, University of Melbourne. Many thanks to Marion for sharing Barbara’s life with us. Three excerpts from Barbara’s memoir have been included at the foot of the post, with the permission of her family and supervisor.

This obituary has been provided by Marion May Campbell, who supervised Barbara Moore’s thesis, The Art of Being a Tortoise: Life in the Slow Lane. The thesis is being edited for submission for a Master of Arts by Research in Creative Writing at the School of Culture & Communication, University of Melbourne. Many thanks to Marion for sharing Barbara’s life with us. Three excerpts from Barbara’s memoir have been included at the foot of the post, with the permission of her family and supervisor.

Barbara began writing educational children’s books. Four of these were published by Pearsons, and translated into many languages. She told me, her eyes sparkling with mirth, that her children’s books sold well in Korea and that she was ‘hot in Siberia’.

Barbara began writing educational children’s books. Four of these were published by Pearsons, and translated into many languages. She told me, her eyes sparkling with mirth, that her children’s books sold well in Korea and that she was ‘hot in Siberia’.