This is a Guest Post by Atlasien. It was originally published here.

I’m a multiracial Asian-American woman, Southerner, third-culture kid and mommyblogger. I’ve been living in the Atlanta area for more than a decade now. I mainly blog about race and foster care adoption. My husband and I have a 7-year-old son that we adopted as an older child. I enjoy this blog, and I’ve learned a lot of important stuff about disability issues by reading here.

What does scoliosis have to do with sex?

There are a lot of connections. I guess I’ll need to start by explaining scoliosis. It’s a common disorder, but one that is often very misunderstood by the general public, as well as many non-orthopedic doctors. Most people vaguely remember a scoliosis check from their school days. Sometimes the kids are lined up in a row, and told to take off their shirts and bend over while a medical professional inspects them from the back. The experience is obviously rather humiliating and tends to cause a lot of nervous laughter.

Scoliosis — a sideways, left-right asymmetry of the spine — is the most common form of spinal deformity. It can also be accompanied by other forms of spinal deformity, like kyphosis (AKA hunchback) and extreme lordosis (AKA swayback). It sometimes comes as a package deal along with disorders of connective tissue, or with cerebral palsy and spinal bifida. In those cases, scoliosis is often diagnosed at a very early age.

The other kind of scoliosis, the much more common kind, seems to come out of nowhere. It’s known as adolescent idiopathic scoliosis or AIS. “Idiopathic” is from the same Greek root as “idiot” and basically means “we have no idea what causes it.” Though recent research has shown that it’s actually genetic, and they’ve even tracked down the genetic location (but only if you’re white, which is bizarre, because there isn’t any significant racial/ethnic difference in prevalence rate). Someone with this kind of scoliosis (usually a girl, as the incidence of more serious curves among women is 7-10 times that of men) is born with a normal-looking spine. Before puberty, the spine begins to bend and curve. Maybe it stays there… maybe it gets worse through puberty. Then maybe it stays there, or maybe it gets a lot worse close to menopause. Without major surgery, it’s essentially a one way road. In scoliosis vocabulary, when curves get worse, it’s called “progression”. “Progression” is bad. Arresting progression is good.

According to this NIH resource, “Of every 1,000 children, 3 to 5 develop spinal curves that are considered large enough to need treatment.” If you adjust for sex, the rate climbs up to almost 1% of all girls. I don’t know of any source that says actually how many girls receive treatment of which types. Treatment means to watch, take lots of x-rays, determine progression, and if it looks like progression is, well, progressing, to brace. Or in very serious cases, go directly to spinal fusion.

That’s the “Milwaukee” variant of brace. It’s the kind I had. It’s made from hard plastic and steel. It’s expensive, ugly, frightening, and extremely uncomfortable. The family nickname for my brace was “The Iron Maiden”. You can climb into it and strap it on and off, and adjustments of the screws will accommodate changing body shape during puberty. I think you’re supposed to wear it until a few years past puberty, when your spine growth finally halts. The brace is an old form of treatment and it’s shown to be moderately effective at arresting progression.

Many girls experience horror and anger when they find out what bracing is going to mean for their lives, and that it won’t even fix them, it will just probably keep them from getting any worse.

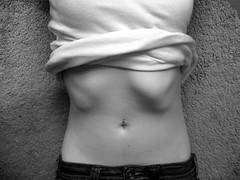

It was easier for me to accept my fate. First of all, my mother also has idiopathic scoliosis, and her curve was fairly serious. Hers is comparable to the woman pictured above. She had not been treated as a girl, and her scoliosis had slowly progressed as she went into middle age. She eventually had a spinal fusion — two long steel rods screwed into her spine — and was in the hospital for two weeks. So I had a strong motivation to make sure my curve didn’t progress as far as my mother’s. She was also a positive role model for me. I saw her as an active, glamorous woman who refused to be limited by scoliosis. I tried to adopt the same stoic attitude toward my own scoliosis. Second of all, my orthopedist said it was OK to only wear my brace 12 hours a day, which meant I slept in it, but I didn’t have to wear it to school. I think he may have subscribed to the philosophy that although the brace should really be worn 23 hours a day, there’s so much social stigma attached to it that many girls rebel, and won’t wear it at all, whereas a private bracing regimen has more likelihood of consistent follow-through.

I don’t know if it would have made school any worse. I’ve written before about the extensive racist abuse, and sexualized racist abuse, I got in late elementary and middle school.

I was harassed so much in the locker room my first year of middle school that I refused to change my clothes at all. P.E. was a living nightmare full of verbal attacks and physical threats from larger girls. I spent much of my time desperately thinking of ways I could get a medical excuse. Unfortunately, aside from my scoliosis, I was healthy as a horse. I refused to participate in activities anyway, and sat with the asthma-sidelined section. I’m still bitter about this experience because it taught me to associate healthy athleticism with emotional trauma and racist bullying. Maybe if I’d had my brace on, I could have gotten my coveted medical excuse.

It was something I never, ever thought of at the time, though. The orthopedist’s word was the word of law. And the brace was something to be hidden. I think this is a common tendency among brace-wearers. Girls that age don’t want to be seen in a brace. For photos, they’ll take off the brace. If they’re told to wear it to school, they’re mocked and stared at. At the time, I considered myself very lucky that I was able to hide my brace from other kids my age.

I don’t know much about disability theory and disablism, but I’ve been reading through blogs about it, and it’s very interesting in relation to scoliosis. I don’t identify as a disabled person/person with disabilities, and I don’t think many other people with idiopathic scoliosis do. But many of us have also gone through an intensely emotional adolescent period where we’re viewed as disabled.

One of the hallmarks of disablism is that it strips away sexuality. The prejudice against disabled people includes thinking they are not supposed to exist sexually, have sexual desire or be desired.

Being braced means going through puberty strapped and screwed in to a weird exoskeleton that incarnates the negation and emprisonment of your sexuality. Your breasts and hips are starting to grow. They might start to bump painfully against the brace. So you have to visit the doctor — often an older man — who adjusts your screws to accommodate your new growth.

The brace seems anti-sexual, but it also has positive sexual connotations. The light at the end of the dark tunnel is that the brace will “keep you normal”. You’ll get through puberty and enter into sexually desirable womanhood without too much spinal deformity… the brace will preserve you. The brace probably becomes the most significant physical object in your life, for good and for evil.

I certainly didn’t receive any counseling about my scoliosis. I don’t know if it’s common today to have counseling as part of the bracing process. If it’s not, it should be. Girls who have gone through bracing feel like it’s them, alone, against the world. Although it’s quite a common experience, by medical and social tradition, the disorder is isolated and hidden.

This study showed that bracing doesn’t affect self-image much. However, it also takes places in Sweden, where school environment I’m sure is quite different than in the U.S. This other U.S. study tells a somewhat different story: “Scoliosis was an independent risk factor for suicidal thought, worry and concern over body development, and peer interactions after adjustment. CONCLUSION: Scoliosis is a significant risk factor for psychosocial issues and health-compromising behavior. Gender differences exist in male and female adolescents with scoliosis.”

After bracing, scoliosis, and deformities of the spine in general, become almost invisible. It’s extremely rare to have a spinal deformity so pronounced that anyone can tell by looking at you when you have clothes on. People with idiopathic scoliosis “pass”. People have known me for years, even decades, without knowing I had scoliosis. Then one day they’ll see me in a bathing suit — and not even the first time they saw me in a bathing suit, but maybe the first time they really focused on my back — and they’ll burst out with something like, “OH MY GOD DID YOU KNOW SOMETHING IS REALLY WRONG WITH YOUR SPINE!!”

Once it stops being invisible, it’s all of a sudden very, very visible. I guess it’s sort of like shaking hands with someone and suddenly realizing they have six fingers.

If I’m not experiencing any back pain, I rarely think about my scoliosis, although I sometimes worry about my future. Pregnancy is not a risk factor for progression, but menopause is. Right now, my thoracic curve is 36 degrees. If it gets past 40, I might need spinal fusion surgery. This is a mostly safe procedure, but it’s still really scary, and involves weeks in the hospital. Click on the following link if you’ve seen enough David Cronenberg movies that you think you can handle it (link to nightmarish spinal fusion surgery image). Spinal fusion partially reverses the curve, arrests or slows down further progression and relieves chronic pain. You’re still reasonably flexible afterwards, but there are potential complications, and I’m not considering surgery at this stage. If I refused surgery, and my curve happened to progress further, I would start to have more pain and diminished lung capacity. Past 60 degrees, I might start to experience severe and constant pain in my back and/or ribs, and my internal organs would get squeezed together and I might start to have breathing problems. Past 80 degrees I might have lung AND heart problems.

But I don’t stay up night worrying about the risks of progression. Many people have more uncertainty about their medical future than I do. For example, if I had diabetes, I might worry about having a foot amputation.

Since I grew up with scoliosis, it’s taken me a while to understand how it looks from the outside. Aesthetically speaking: not good. We’re conditioned to associate left-right symmetry with health and general well-being. People with moderate scoliosis, like me, often look symmetrical from the front, but asymmetrical from the back, and I suppose that seems eerie and perhaps even deceptive and sneaky. There’s a lot of really negative associations in popular culture (e.g. Hunchback of Notre Dame). When mean-spirited people do “retard” imitations they’ll often hunch up one shoulder and stagger in order to simulate a deformed spine.

I don’t talk about scoliosis casually because a) I don’t have any major health problems because of it, so there’s not that much to talk about b) I’m afraid of it being used against me. I’ll put it on medical history forms when I know I can be assured of privacy. It was used against me recently when I applied for private disability insurance. I thought it would be a good idea to have a separate private policy in case I lost my job for any reason. I did a ton of research, spent a lot of time talking with the salesman, and ended up with a quote that specifically excluded anything going wrong with my reproductive system AND my back. I changed my mind and decided it wasn’t worth buying since so much of my body was apparently un-insurable. They excluded my ENTIRE BACK. Hypothetically speaking, if I got in a minor car accident, and as a result developed the exact same kind of back problems that anyone without scoliosis would develop, nothing would be covered. What a terrible deal. No thanks!

The health implications of my scoliosis are not that extreme, and I don’t need any accommodations to perform any major life activities, which is why I don’t consider myself disabled.

– I have foot pain in my arch if I don’t wear comfortable shoes. I can wear platforms, but I can’t wear high heels.

– I have to be a bit careful doing things like yoga and pilates.

– I have to stay reasonably active in order to be 100% pain-free. When I get too sedentary, I start having back pain and rib pain. If I ever had an illness that forced me to rest all the time, I’d be in big trouble. Exercise and stretching are highly effective for scoliosis back pain. Other options I would consider to control pain if it ever got worse include drugs, physical therapy and adult braces. There are a gazillion alternative health “cures” for scoliosis back pain suffering, but they strike me as being of very dubious efficacy.

– I have to watch my posture

– I have to watch my weight. Excess weight leads to back pain. Being underweight might be even worse, because being underweight is connected to bone density loss, and people with scoliosis have lower than average bone density anyway.

None of these problems are really unique to scoliosis. Plenty of able-bodied and disabled people have back pain or foot pain.

This link from Eurospine.org sums it up: “Progression of scoliosis can involve an aesthetic problem and lead to functional problems. Respiratory disorders may develop in large curves greater than 80 [degrees]. Nonetheless, the mortality rates and vital prognosis in individuals with scoliosis are comparable to those of the general population.”

It’s the “aesthetic problem” of scoliosis that’s unique. Like I mentioned before, left-right symmetry is wound up with definitions of health and beauty across many different cultures. People like me are aware of this on a subconscious or barely conscious level. 99.99% of the time I forget that I don’t fit that symmetrical standard. Every so often I’m reminded, and it feels a bit painful. There are subtle psychological effects. Vague feelings of being a secret curved impostor in a straight-backed world. Times when I feel like my spine is an enemy working against me… times when it hurts to breathe and the pain makes me feel angry at my spreading rib bones, and I wish I could reach inside of myself and squeeze them back into place. Sometimes I’m bitter about the inches of height I lost to scoliosis.

Back to sex. Even without bracing, there’s still a sexual paradox when it comes to scoliosis. Have you ever seen a picture of a woman with scoliosis and/or kyphosis that was not anonymous, depersonalized, clinical, grim and depressing? Like the photos I included above? Scoliosis is profoundly unsexy.

On the other hand, when women pose provocatively, they often throw one hip to the side and put one shoulder forward.Why is that pose sexy? Maybe it makes us look femininely defenseless and vulnerable, as opposed to a masculine, stick straight pose. That’s going along with a typical sexist definition of “femininity”. There’s another less sexist possibility… the pose is also highlighting the flexibility of the spine. So in that sense, the woman is showing off her body’s capacity by bending in a certain way.

There’s a comic book artist, Rob Liefeld, who was (in)famous starting in the 1980s for drawing unrealistic women. The conventions of drawing women are in comics are easy to criticize, but Liefeld’s stuff is… well…I guess you’d have to see the spinal curvature to believe it.

That’s supposed to be sexy. For the audience of predominantly young men who made Liefeld very popular, it must have been sexy. This is a funny analysis of the above drawing by a group of women comic book artists:

Take note of Avengelyne’s waist and how it is thinner than her head. Minus the hair. Note how it hangs beneath her ribcage like a suspension bridge, rather than actually supporting the top of her body. (Her torso must be kept afloat by those helium breasts.) Note the scoliosis gone grossly untreated. Note the little leather bags which wouldn’t fit around a normal person’s wrist. Especially note that the artist put her in the most obvious POSE to exaggerate the spine: a profile shot with negative space between her back and arm. That’s correct – our intrepid heroine’s spine would appear yanked. Avengelyne is a SWAYback™.

The humor is partly at my expense. But I can’t help laughing. It’s a highly sexualized image, but not one that I identify with in any way.

But here’s a poster image I ran across that uses stupid sexist humor to make fun of a real woman, and I don’t find it funny at all.

It really illuminates the double standard that women are subjected to. You’re supposed to be sexy so that you please men. But if it looks like you’re trying TOO hard, men (and other women) will make fun of you. If you don’t wear makeup, you’re a [insert homophobic slur]. Wear too much makeup, you’re a [insert transgender-phobic slur]. Curve your back, look sexy. Curve it too much, it looks like you’re deformed. Argh!

Thanks to my brief readings of disability theory, I realize that making fun of people with spinal deformities isn’t something I should just accept as the natural order of things, especially because this humor is connected to moral judgments of disability. That is, the idea that physical body difference reflects some kind of moral failing. When it comes to scoliosis, I think the general public halfway believes that scoliosis is the fault of the person’s family. There’s a myth that giving young kids backpacks that are too heavy will make their spines curve (totally not true). When people are adults, “she should have had that corrected” is sometimes an assumption. A lot of people don’t realize that the only sure way to even partly reverse a curve is spinal fusion, which also leaves a giant seam-scar running up your back. Another judgment is that a person with scoliosis must be poor. It’s true that I’m very lucky I had access to bracing; if I wasn’t born into a middle-class family in a rich country, my curve would be a lot worse by now. So there are major class differences in scoliosis, but ultimately, we’re all in different positions on the same boat because there is no way to permanently and completely reverse adult scoliosis.

Thanks to flickr, I did actually find some images of scoliosis that I think are beautiful and help affirm positive self-image and sexuality. I wish I’d found a greater variety of body types, but these images are great to start off with. Some are post spinal fusion.

First, here’s the typical clinical picture. It shows everything that’s wrong with the body.

Now here are the flickr pictures. They show the open possibility and vitality of a body with scoliosis.

When I walk, my right hip swivels a bit higher and wider than my left hip. I’ve had people tell me it looks sexy. I’ve had people ask if I’ve hurt my foot. Neither reaction bothers me anymore. The way I walk is just the way I walk. It gets me where I need to go.

Acknowledgements for this post: thanks to Thorn for commenting about this issue, and mentioning how it negatively affected your adoption homestudy due to ignorance on the part of the social worker. Also thanks to Deesha Philyaw on Twitter for mentioning the Judy Blume book about a girl who goes through bracing: Deenie. I wish I’d gotten a chance to read that book when I was a girl, and it sounds really interesting.